October 3 - 28, 2022. Tsimshian: Art of the Indigenous People of the Pacific Northwest

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the anonymous private collector who lent the majority of the works in this show and to the University of Dubuque for the loan of the Boxley totem pole.

Organizing the show has given me the opportunity to renew my acquaintance with Bonnie Sue Lewis, Professor of Mission and World

Christianity Emerita. I am grateful for her insights and for her very readable book.

The generosity of our alumni, Bill and Judith Crandall, has made a publication available to a general audience and we are quite indebted.

Finally, there’s a kind of internal pride one feels when a former student demonstrates accomplishment of a process. This is exactly the case for this show. As recent Digital Art and Design graduate and now Coordinator of the Bisignano Art Gallery, I am proud to acknowledge the work of Noah Bullock and grateful to him for proposing, designing posters and hanging the exhibit currently in the Gallery.

Alan Garfield

Director, Bisignano Art Gallery

Tsimshian Exhibit Poster

Gallery Director Essay

The origins of the current show, Tsimshian: Art of the Pacific Northwest, are complex. Like the art itself. And while the show’s about art, surely, in this context at this University, it is about much more. You see, this show is historically tied to a tradition at the University of which most students and faculty are unaware. Under the leadership of Professor Henry Fawcett, the University of Dubuque Seminary actively acknowledged native Alaskan indigenous peoples by training them as pastors here in Dubuque.

If there was to be a dedication of this show, I’d dedicate it to the late Rev. Dr. Henry Fawcett, seminary professor and a relentless advocate for the dignity, self-respect and civil rights of Alaska native and Native American peoples during his entire adult life, both in and outside of the classroom. Himself from Metlakatla, Alaska, Fawcett was a member of the Tsimshian Nation. If students were aware of our Alaskan heritage, perhaps it was because since 2000, they often walked past a totem pole, prominently placed in the Myers Library. This work was done by David Boxley, Tsimshian artist and Woodward artist-in-residence at UD. Except for temporarily taking up residence in the Bisignano Art Gallery for the length of this show, this carving now normally stands proudly welcoming all to the University in our new Welcome Center. And we’re all very thankful to our Maintenance staff for orchestrating this temporary move.

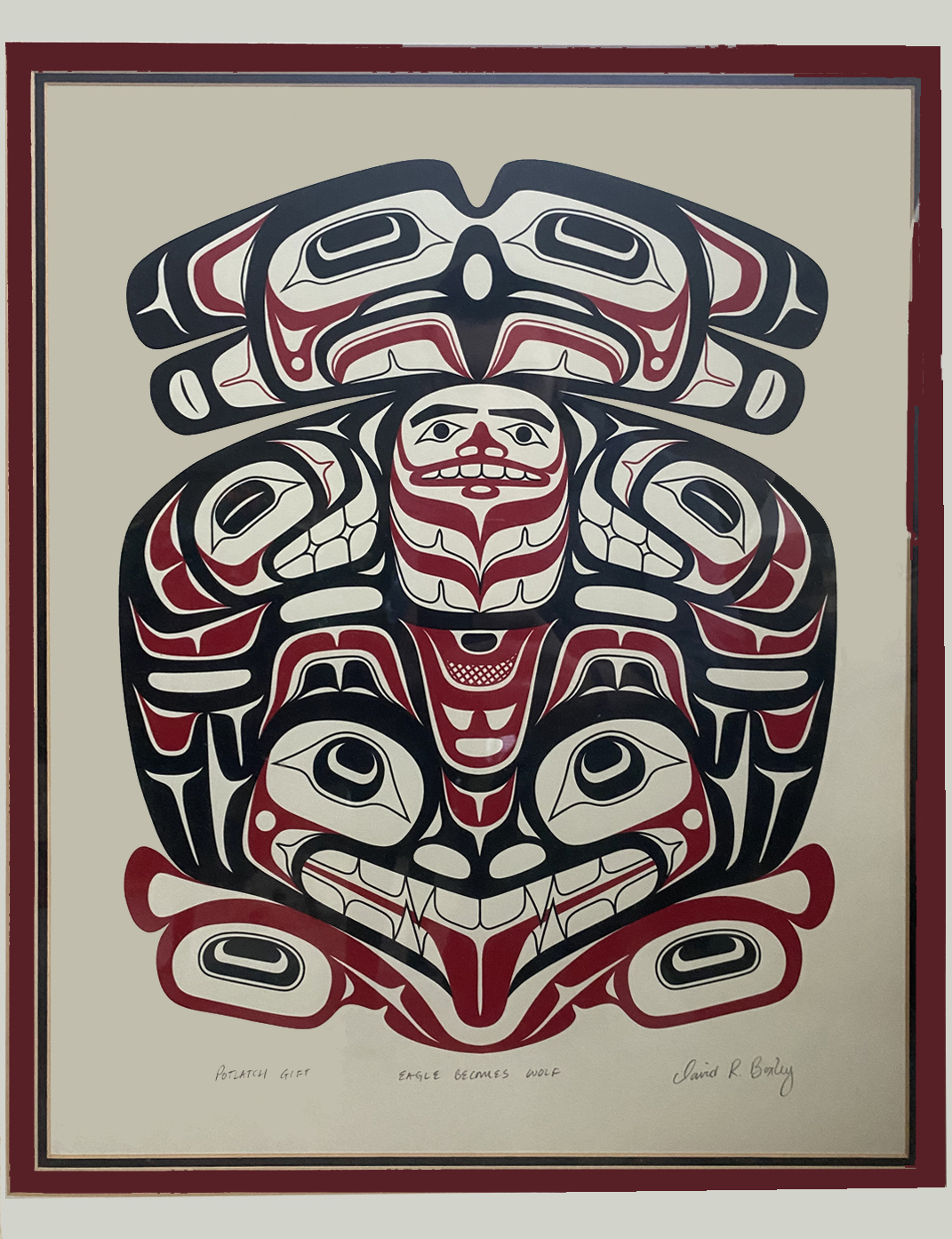

Naively, I never knew people could be both Native American (in this case Tsimshian) and Christian. But in our colleague’s 2003 book, Creating Christian Indians (her dissertation), Professor Bonnie Sue Lewis points to broad similarities between Christianity and native cultures, such as an emphasis on morality, generosity, and native approaches to spiritual power. Thus, you’ll see an amalgam of various animals with prominent crucifixes. Lewis’ thesis is clear in these images; Christianity is taken seriously in the social and cultural lives of the Tsimshian. Her study and cultural insights help place the show in its proper context.

Like many of you, my focus has always been on Western European art and culture, so this show has been quite the journey. While new at exploring the art and cultural traditions of the Tsimshian, I humbly admit my indebtedness to Viola Garfield’s book (no relation) The Tsimshian: Their Arts and Music published by the American Ethnological Society in 1951. The book is online, a free offering from Google. See https://books.google.com/books?id=EJjhAAAAMAAJ.

A third resource I recommend is a most readable ethnographic study by the University of Chicago’s Christopher Roth. See Roth, Christopher F. “Goods, Names, and Selves: Rethinking the Tsimshian Potlatch.” American Ethnologist, vol. 29, no. 1, 2002, pp. 123–50. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3095023.

Who are the Tsimshian, or “People of the Skeena”

The Tsimshian are a group of linguistically and culturally related people who can be divided into four sub-language categories:

- the Gitxsan, who occupy the Upper Skeena River;

- the Nisga’a (Nishga) along the Nass River;

- the Coast Tsimshian, which the Gitselasu are often grouped with, along both the lower parts of the Skeena River and the nearby coast;

- the Southern Tsimshian, who are found along the coast as well as the southern islands.

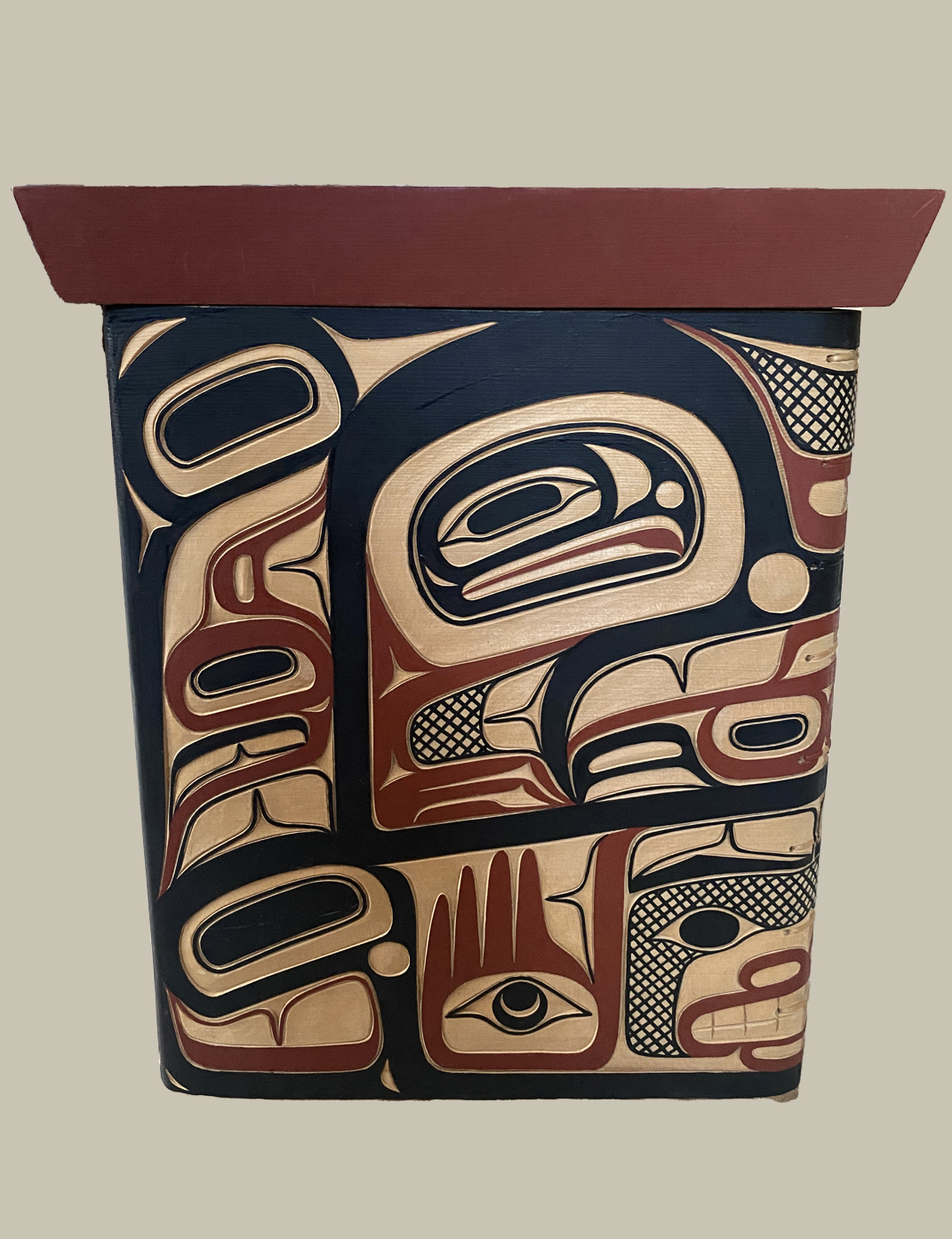

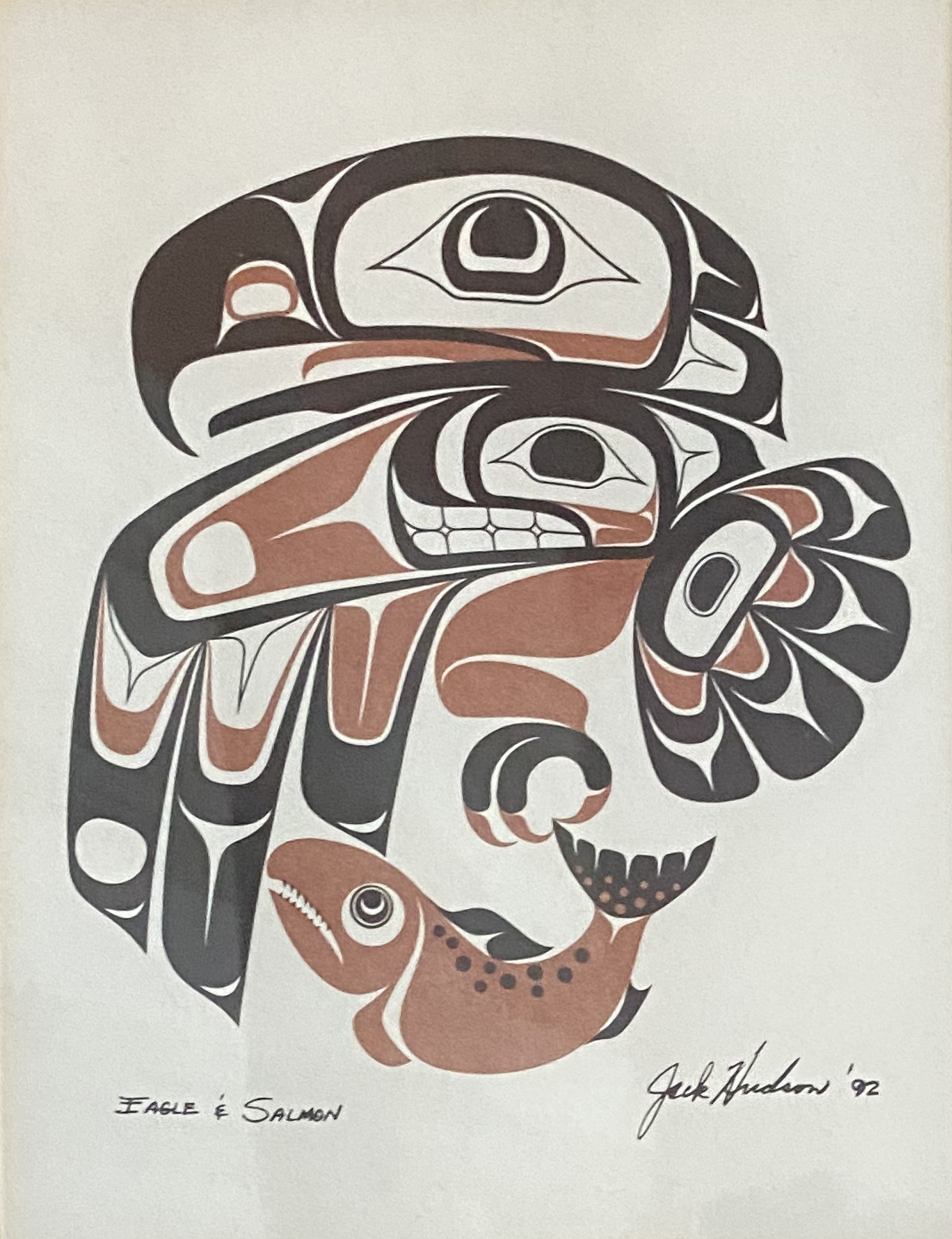

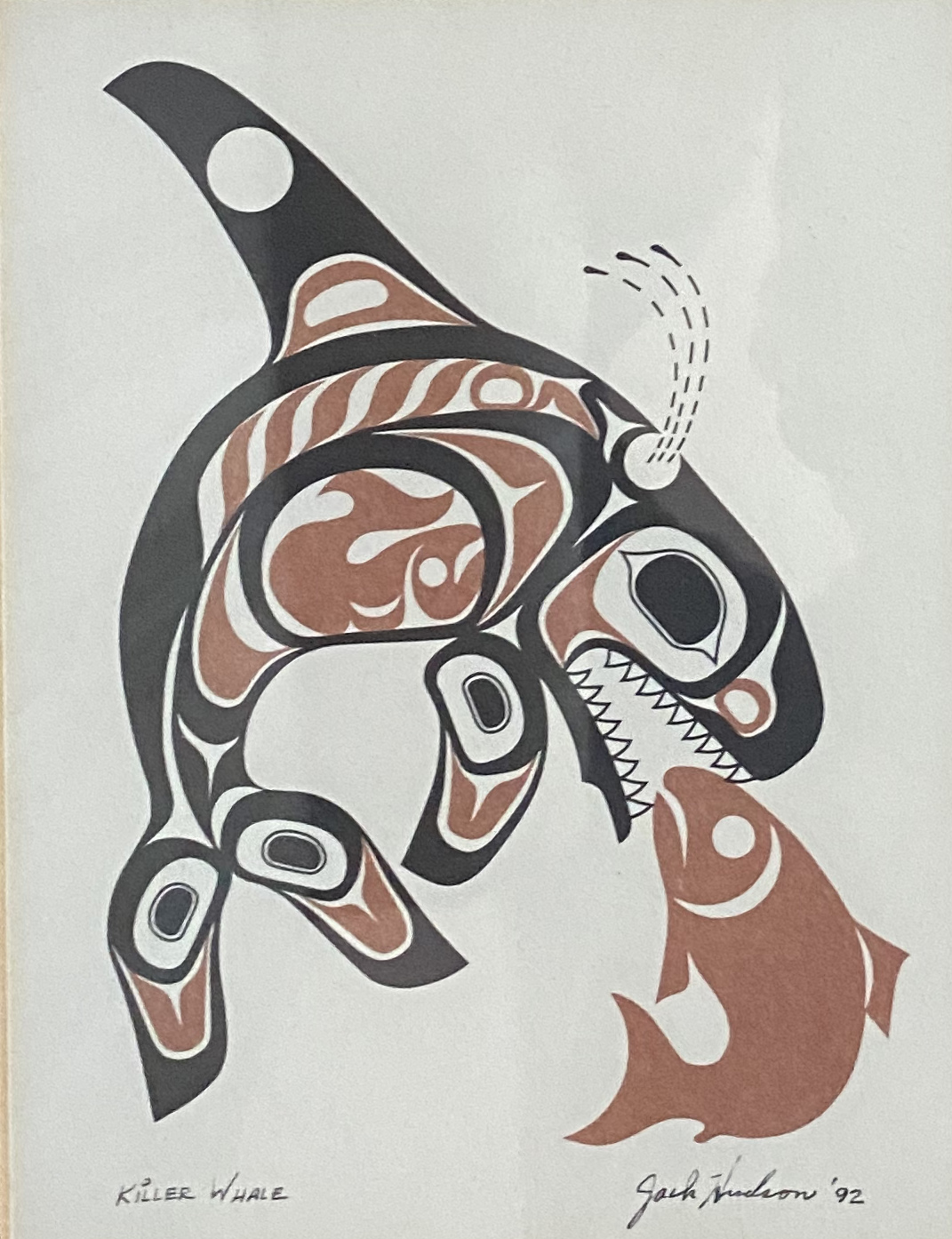

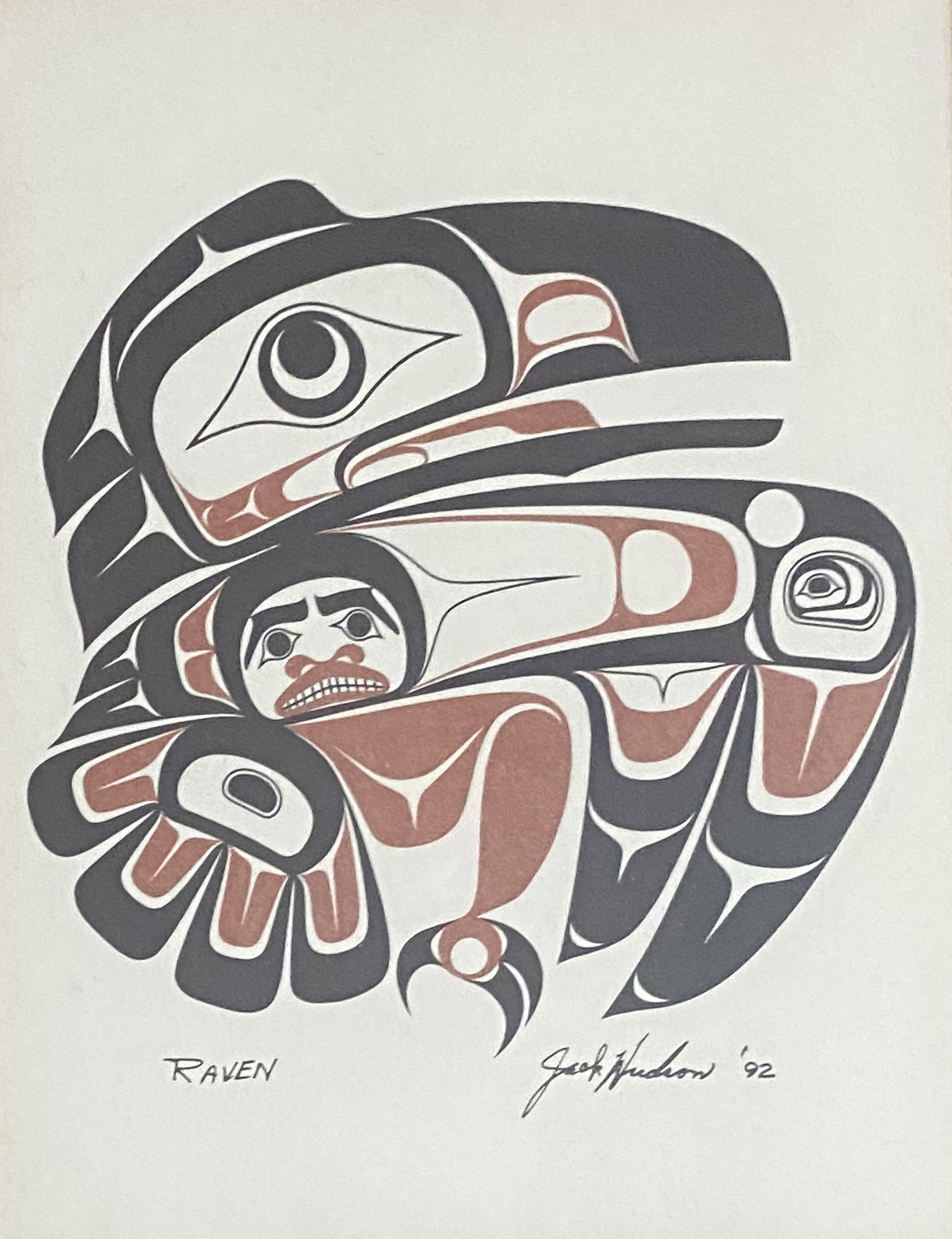

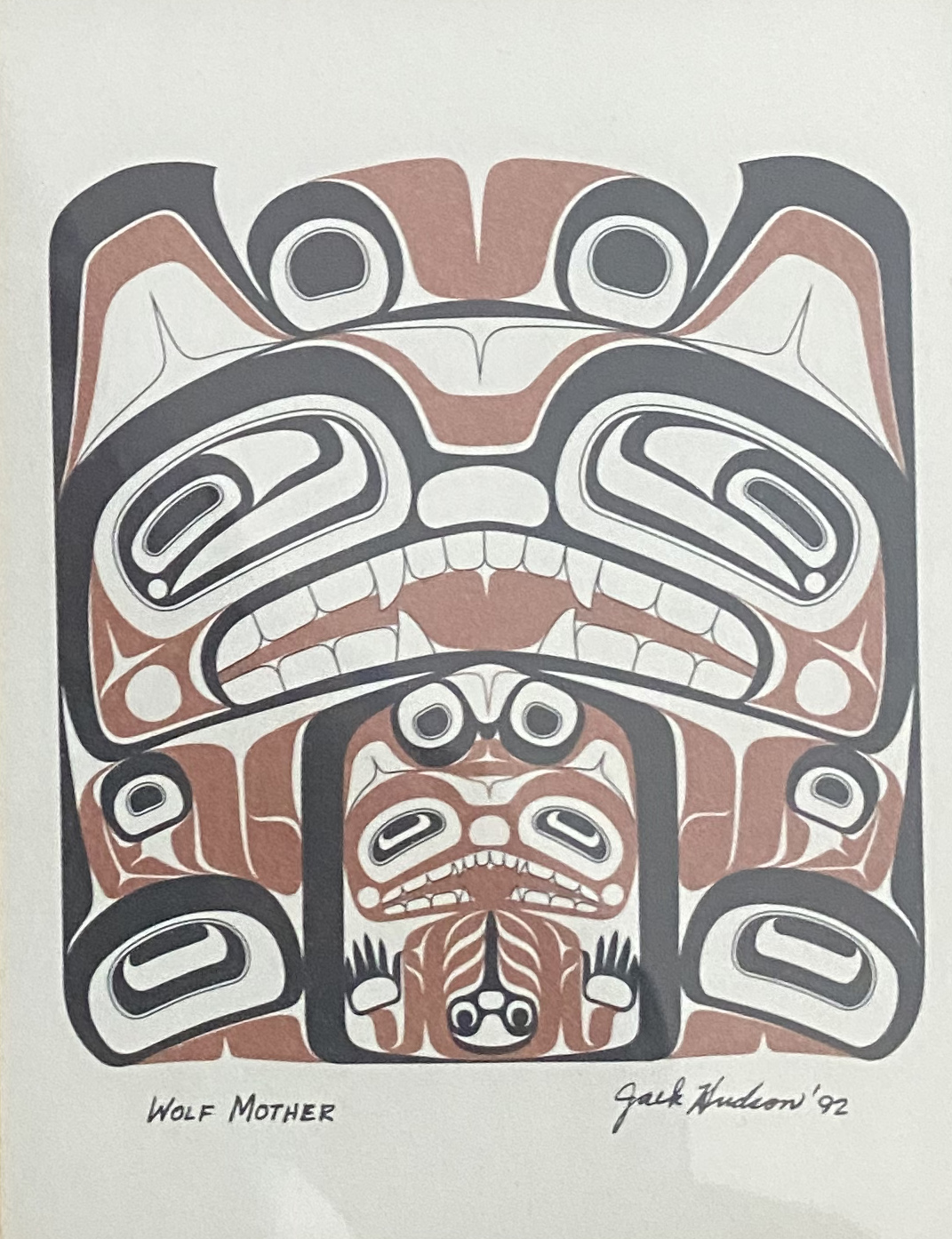

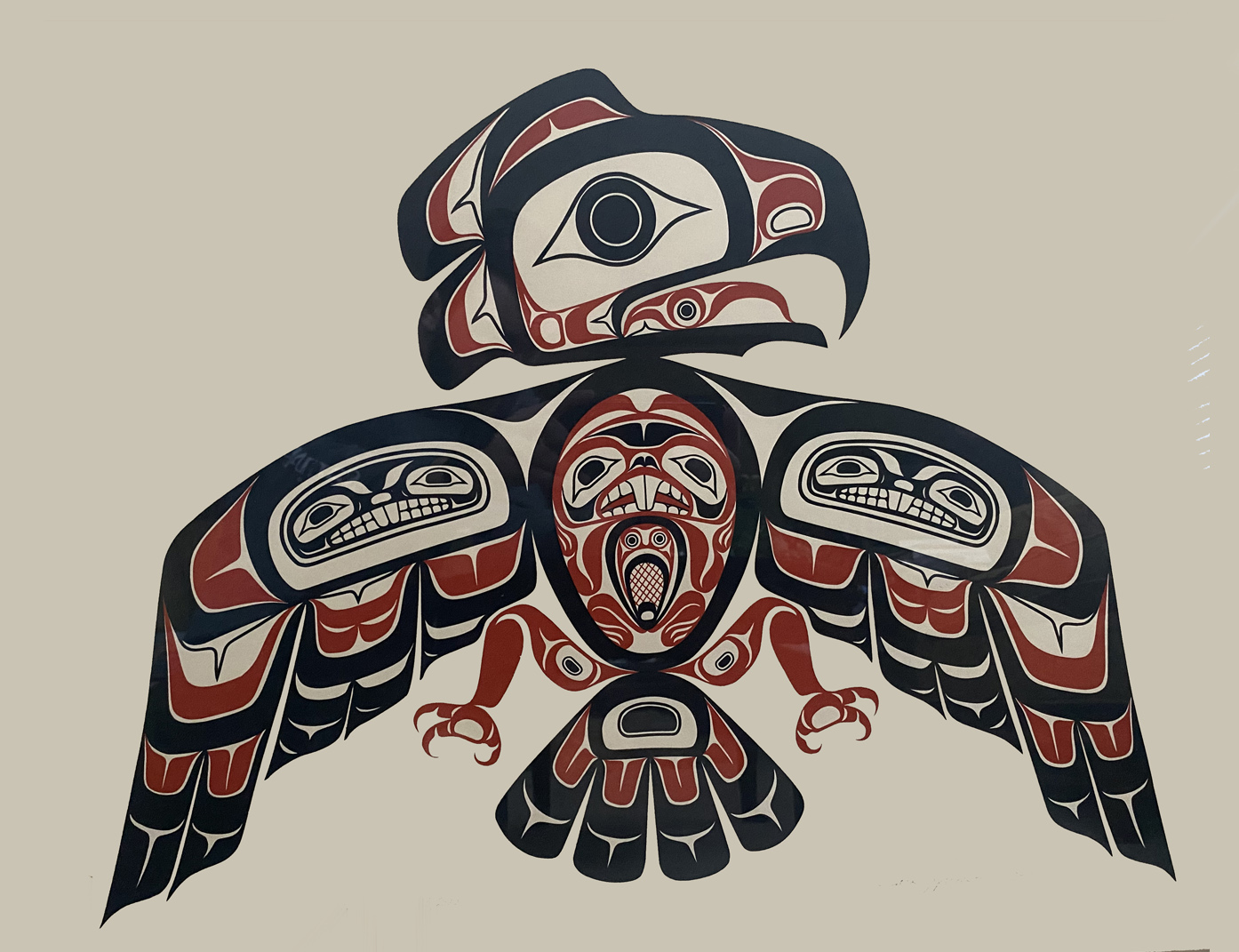

While I have never visited the Pacific Northwest (or Alaska), the Tsimshian style has come in a big way and has taken over the Bisignano Art Gallery. It is clearly a bold, beautiful, and intricate art form. Perhaps not surprising, given the sad history of interaction between the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest and Western settlers, at one time Tsimshian art was forbidden. Yet now, it is now experiencing a kind of revitalization - a renascence of sorts – that can be seen in the study and understanding of a complex design system called ‘formline’ as well as in the different carving techniques used to create totem poles, masks, rattles, panels, bentwood boxes, and other forms of art.

One such modern master artist is well represented in this show, David Boxley. Boxley is a Tsimshian artist and carver also from Metlakatla, Alaska. While he lives and teaches in Seattle, Boxley’s inspiration comes from the ancestors of his Tsimshian Tribe (Northern British Columbia and Southeast Alaska). He has dedicated over 40 years in interpreting and modernizing Tsimshian arts and culture. His grandparents shared their hunting, fishing, and gathering cultural practices. As an artist and culture-bearer, Boxley has been deeply involved in the rebuilding and teaching of native art, traditions, and language. His art demonstrates that a culture threatened by extinction can still be alive and thriving. A prolific artist, Boxley has produced thousands of works for patrons around the world. He is also the founder of a performance group that translates his art into song and dance while teaching and sharing Tsimshian oral stories through masks and other carved designs.

The Pacific Northwest is a large, diverse geographical area. And traditionally, the Tsimshian tribes would often occupy a single winter village and then move to their seasonal fishing grounds in spring and early summer. In the fall, after fish and other winter supplies were preserved and stored, small groups would move on to their traditional hunting territories. Their lifestyle, like their art, was unique.

The iconography of Tsimshian art is based on the complex organization of clans, secret society performances and by potlatches, which are large feasts where name, rank or hereditary privileges are claimed through dances, speeches and the distribution of property. Most Tsimshian objects and images depict myths, tales, and their associated supernatural beings. Humans, animals, birds, and fish are also portrayed. Crests are represented through carvings and paintings on interior posts, totem poles, house fronts, beams, rafters and ceremonial entrances.

Stylistically, Tsimshian colors include blues, reds, yellows, blue-greens, black and white, where reds and blacks are prominent. Unique features found on Tsimshian poles include mask-like faces that are usually without a body, and figures of animals or birds (usually carved separately and attached) on top of poles that appear to be in motion or flight. Often, Christian symbolism is subtly integrated.

Alan Garfield

Director, Bisignano Art Gallery