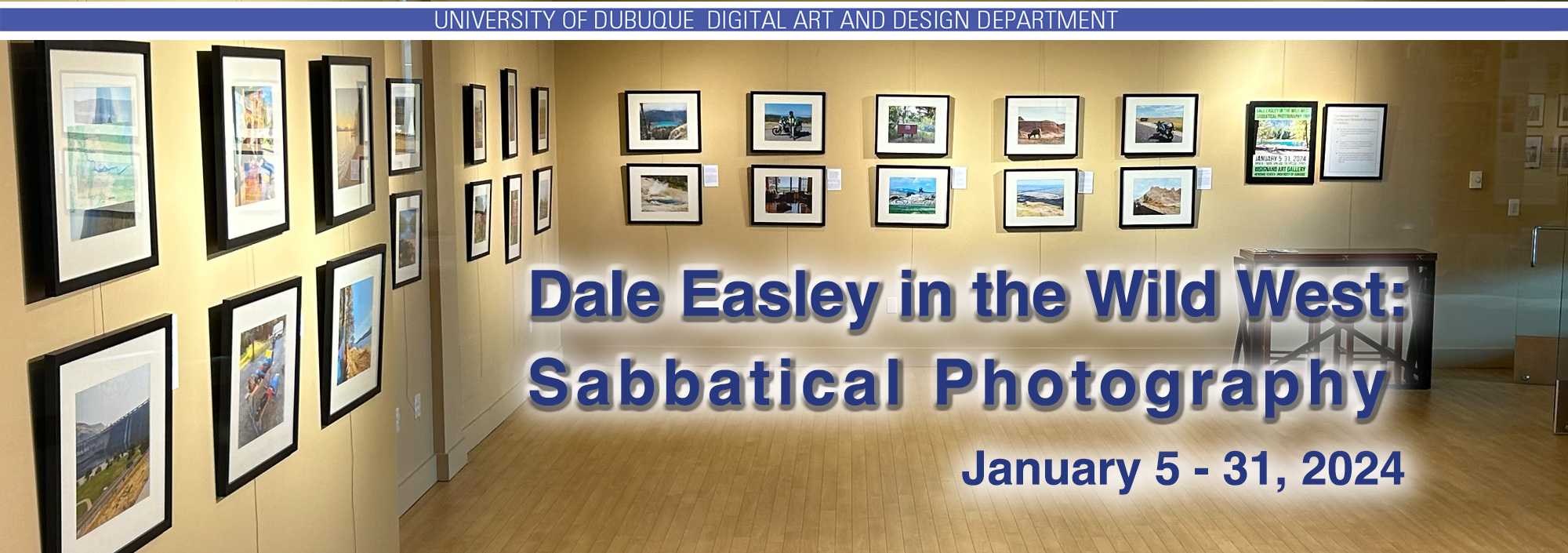

Dale Easley in the Wild West: Sabbatical Photography

January 5 - 31, 2024.

Dale Easley's Text

ESSAY

Ever notice how an essay or review on an artwork or a poem can present it in a new light, sometimes in a pecular light? I certainly have and, to be quite honest, sometimes it is not in the best interest of that art work or that artist. But, after all, what do art critics know? I mean, really? So I offer this preamble as a word of personal 'dread' for the work of my friend and colleague, Dale Easley. And I hope he's not too offended by what follows.

To me, this show is a bit like the Beat Generation poetry revisited. Now if you know Professor Easley, then you know he is an avid and accomplished writer - prose, poetry, and (naturally) science papers. And as I look at the images of this show and read his text, my mind wanders back to Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady - their friendship, their thunderous letters, and their On The Road adventures. Zoom ahead 75 years, and here you have a scientist/writer/photographer on his own personal odyssey, combining cross country and cross discipline.

There's a clear mirror image here of Kerouac's three week, self-made myth, in Dale's text-and-image journey. Legend has it that Kerouac wrote his On the Road, typing it almost nonstop on a 120-foot roll of paper. (The truth is that the book actually had a much longer, bumpier journey from inspiration to publication, complete with multiple rewrites and repeated rejections.) And I suspect the same can be said about the works that we see here.

Journeys have a way of changing us. That's why we travel, I think, to experience compassion and empathy for our world and (if we're lucky enough) for ourselves. And that's what a sabbatical is supposed to do - assist in nuturing in achieving freshness and new ideas. It has been a pleasure working with Professor Dale Easley in putting this show together. He was full of self-doubt in the beginning; I wasn't. The 120+ feet document in the Gallery is a great reflection of Dale's probing mind. Sincere thanks go to him and to Noah Bullock, Coordinator of the Gallery, for printing the images and text and designing/hanging the show.

Alan Garfield, Director Bisignano Art Gallery

Ever notice how an essay or review on an artwork or a poem can present it in a new light, sometimes in a pecular light? I certainly have and, to be quite honest, sometimes it is not in the best interest of that art work or that artist. But, after all, what do art critics know? I mean, really? So I offer this preamble as a word of personal 'dread' for the work of my friend and colleague, Dale Easley. And I hope he's not too offended by what follows.

To me, this show is a bit like the Beat Generation poetry revisited. Now if you know Professor Easley, then you know he is an avid and accomplished writer - prose, poetry, and (naturally) science papers. And as I look at the images of this show and read his text, my mind wanders back to Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady - their friendship, their thunderous letters, and their On The Road adventures. Zoom ahead 75 years, and here you have a scientist/writer/photographer on his own personal odyssey, combining cross country and cross discipline.

There's a clear mirror image here of Kerouac's three week, self-made myth, in Dale's text-and-image journey. Legend has it that Kerouac wrote his On the Road, typing it almost nonstop on a 120-foot roll of paper. (The truth is that the book actually had a much longer, bumpier journey from inspiration to publication, complete with multiple rewrites and repeated rejections.) And I suspect the same can be said about the works that we see here.

Journeys have a way of changing us. That's why we travel, I think, to experience compassion and empathy for our world and (if we're lucky enough) for ourselves. And that's what a sabbatical is supposed to do - assist in nuturing in achieving freshness and new ideas. It has been a pleasure working with Professor Dale Easley in putting this show together. He was full of self-doubt in the beginning; I wasn't. The 120+ feet document in the Gallery is a great reflection of Dale's probing mind. Sincere thanks go to him and to Noah Bullock, Coordinator of the Gallery, for printing the images and text and designing/hanging the show.

Alan Garfield, Director Bisignano Art Gallery

A Sample of Text from the Show

We believe that life's greatest moments and deepest connections exist outside your comfort zone. I believe that underneath the discomfort holding us back, there’s fear. The trick is to feel that fear, and do it anyway.Yes Theory, Talk to StrangersOn August 13th, 2022, I threw my good leg over the saddle of my Honda Africa Twin and headed west, setting out from my home in Dubuque, Iowa, on what became a 5177-mile, 6.5-week quest. It wasn't a religious journey like walking the Camino de Santiago, though I was in search of something missing in my life, nor was it a buddy trip like On the Road, as I traveled alone. I was looking for something, but I couldn't name it, and my biggest fear was returning unchanged, just drifting through my final years into death or, worse, senility.

In recording my impressions of the natural scene I have striven above all for accuracy, since I believe that there is a kind of poetry, even a kind of truth, in simple fact. But the desert is a vast world, an oceanic world, as deep in its way and complex and various as the sea. Language makes a mighty loose net with which to go fishing for simple facts, when facts are infinite. Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness

When I was 19 years old and had just finished my freshman year of college, I took a month-long geology course, backpacking and camping, washing off under hand pumps, showering once a week. We started from North Carolina, crossing the Mississippi River on our second day, progressing towards the Badlands. This was a time before the internet and cell phones. Instead, we had journals and a box of books. In the evenings after setting up camp, cooking, and eating, we had time to write about the day’s events, our thoughts, and the beauty we observed. And we had time to read.

One of the books I read on the trip was Desert Solitaire by Edward Abbey. The solitude he found and his reflections inspired me at that time when I was on the cusp of adulthood, trying to determine how I wanted my future to unfold. Though it has taken me decades to realize that I was more a misfit than an introvert, taking off alone on a motorcycle adventure was my own solitary time of reflection.

In my sabbatical proposal that enabled the trip, I had stated that I wanted to revisit places from my youth and write about how climate change had affected them. However, I was approaching major transitions in my own life—the marriage of my daughter, advancing arthritis, retirement, and age at which my father died. Perhaps for the last time, I wanted to seize the day.

The biggest hindrance to learning is fear of showing one's self a fool. William Least Heat-Moon, Blue Highways

When William Least Heat-Moon headed out to circumnavigate the U.S. on lesser-used two-lane highways—blue on the old Rand McNally Road Atlas—his marriage was dissolving and his teaching career had ended. As part Osage, he faced not fitting in wherever he went. And yet, he went. He set off on his journey in 1978 in a Ford van and traveled 13,000 miles during four months, far more than I was to. But we shared a desire to understand how humans and the environment interact and change each other.

On that first geology trip when I was 19, we camped near the Shoshone River between Cody WY and Yellowstone National Park. The campsite had large evergreens, little underbrush, and a view of the river. Decades later, all those trees have been cut down, victims of the pine beetle. Winters aren’t as cold as they once were, and the beetles’ range has expanded.

But when I first camped, there were no bear boxes either. The grizzly bear was in danger of extinction. This time, the campground host told me that she had seen multiple signs of bears at nearby Forest Service campgrounds. All food, cooking gear—even propane—had to be stored in those bear boxes to avoid attracting the bears to my camp. So, we’ve had some successes with conservation.

Ozymandias By Percy Bysshe Shelley

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

While in Montana, I dropped by to see my nephew who taught at Montana State University. He has three kids and lives in a two-bedroom apartment, paying over $3000 per month. Yet Montana has the 48th smallest economy among states. My daughter is in grad school in Idaho, ranked 39theconomically, and the month of her wedding, her apartment rent was raised over 50%. What’s going on?

The West is not new to boom-and-bust cycles. Extraction industries—mining and logging—boom, strip what they can, then leave town, usually leaving their mess behind. But today’s boom is different, driven by outside money plus remote workers. During the pandemic, we rapidly improved the possibilities for doing many jobs from anywhere there’s an internet connection. And university towns have good internet. Plus they tend to have a variety of food and entertainment. Add to that the beauty of the West, and money and people from the tech sector in California, Texas, and Washington poured in, driving up real estate and rent prices. For longtime residents, life suddenly became a lot more expensive.

For I have always lived violently, drunk hugely, eaten too much or not at all, slept around the clock or missed two nights of sleeping, worked too hard and too long in glory, or slobbed for a time in utter laziness. I've lifted, pulled, chopped, climbed, made love with joy and taken my hangovers as a consequence, not as a punishment. I did not want to surrender fierceness for a small gain in yardage. My wife married a man; I saw no reason why she should inherit a baby.John Steinbeck, Travels With Charley

In late August, I was in a campground bathroom in West Yellowstone chatting with a guy at the sink next to me. He had a big belly, a gray ponytail, and was a Harley rider who had just come from Sturgis, the big motorcycle rally in South Dakota. Afterward, I went to a hut in the middle of the campground that sold coffee, bought some and a muffin, and sat down at a picnic table to journal. The guy came over and joined me. It turned out that he was a Ph.D. from Florida who works on space launches for NASA. He has a drum studio in his basement. His wife is a suicidal invalid, so he only leaves her once a year to come out West to meet up with his brother to go motorcycle riding. To say that my initial stereotype of him was wrong would be an understatement. I was humbled.

I have come to believe that a great teacher is a great artist and that there are as few as there are any other great artists. Teaching might even be the greatest of the arts since the medium is the human mind and spirit.John Steinbeck, On Teaching

I have been a teacher for most of 40 years. I taught high school math for two years in Kenya, water resources for a year in the Middle East, geology grad school for 15 years in New Orleans, where I also volunteered as a GED teacher, and from 2005 till now at the University of Dubuque. My identity has been teacher, but the sabbatical year with which the trip west began was leading a year later to retirement. My identity was soon to change.

For years, students in my introductory geology lab course have used historical photographs of Grinnell Glacier to estimate the rate of its melting and the date at which it may disappear. I wanted to take a photo to show them I’d been there, but on my 10-mile hike that day, clouds kept it unseen. The hike was longer than I expected because the trail I originally planned to hike was closed because of grizzly bears.